Venous ablation is a technique for the treatment of venous reflux in legs using diathermy or laser equipment.

Venous stasis is a common condition in which the flow of blood from the legs to the heart is abnormal.

Venous stasis is a common condition in which the flow of blood from the legs to the heart is abnormal.

Most people assume that the heart pumps blood out to the legs and then pumps it back. That's only half right. Actually, the heart only pumps the blood out. Leg muscles pump it back. Every time a leg muscle tightens (called contraction), it squeezes the leg veins flat. Blood is pushed through the veins like toothpaste being squeezed from a tube.

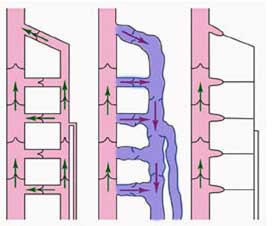

When everything is working normally, a series of one-way gates (called valves) makes sure that the blood can only move one direction: toward the heart. However, when the valves are damaged, the "muscle pump" doesn't work (imagine a busy intersection with no traffic signals). This condition is called reflux and most often involves a large leg vein called the saphenous vein.

When saphenous reflux is present, blood simply pools in the legs, causing everything from unsightly varicose veins to severe pain and ulceration of the skin. [Fig. 1]

In the normal situation, valves in the vein wall keep blood flowing toward the heart (green arrows). When the valves are damaged, blood can flow backwards (red arrows) dilating the vein and pooling in the leg. When the vein is ablated, normal blood flow direction is restored.

The easiest treatment is to wear compression stockings. These special socks gently squeeze the leg, helping the muscle pump to work more effectively. If compression stockings do not help, the abnormal vein must be eliminated. Historically, this has been done with a surgical procedure called "vein stripping." It can now be done with a less invasive technique known as venous ablation.

Venous insufficiency resulting from superficial reflux because of varicose veins is a serious problem that usually progresses inexorably if left untreated. When the refluxing circuit involves failure of the primary valves at the saphenofemoral junction, treatment options for the patient are limited, and early recurrences are the rule rather than the exception.

In the historical surgical approach, ligation and division of the saphenous trunk and all proximal tributaries are followed either by stripping of the vein or by avulsion phlebectomy. Proximal ligation requires a substantial incision at the groin crease. Stripping of the vein requires additional incisions at the knee or below and is associated with a high incidence of minor surgical complications. Avulsion phlebectomy requires multiple 2- to 3-mm incisions along the course of the vein and can cause damage to adjacent nerves and lymphatic vessels. Venous ablation eliminates the abnormal, refluxing vein by sealing it closed. The vein does not actually have to be removed from your body, as in vein stripping. Venous ablation is done through a tiny incision at the knee (the size of a pencil point), a small tube is placed into the saphenous vein. Then, a laser or radiofrequency fibre is passed through the tube into the vein. Once in place, the fibre is activated, delivering very localized heat to the vein wall. In response, the vein closes down and becomes permanently blocked. [Fig. 2]

Fig 2 - The catheter is inserted into the dilated vein. It is then activated and withdrawn, causing the vein to close down and become sealed off.

Fig 2 - The catheter is inserted into the dilated vein. It is then activated and withdrawn, causing the vein to close down and become sealed off.

Venous ablation treats only the abnormal vein that is allowing blood to flow backwards. Since this vein has lost its ability to carry blood in the correct direction, it is no longer needed.

Technology:

The original radiofrequency endovenous ablation system worked by thermal destruction of venous tissues using electrical energy passing through tissue in the form of high-frequency alternating current. This current was converted into heat, which causes irreversible localized tissue damage. Radiofrequency energy is delivered through a special catheter with deployable electrodes at the tip; the electrodes touch the vein walls and deliver energy directly into the tissues without coagulating blood. The newest systems delivers infrared energy to vein walls by directly heating a catheter tip with radiofrequency energy.

The original radiofrequency endovenous ablation system worked by thermal destruction of venous tissues using electrical energy passing through tissue in the form of high-frequency alternating current. This current was converted into heat, which causes irreversible localized tissue damage. Radiofrequency energy is delivered through a special catheter with deployable electrodes at the tip; the electrodes touch the vein walls and deliver energy directly into the tissues without coagulating blood. The newest systems delivers infrared energy to vein walls by directly heating a catheter tip with radiofrequency energy.

Energy delivery: In the original radiofrequency catheter system, the catheter was pulled through the vein while feedback is controlled with a thermocouple to a temperature of 85°C to avoid thermal injury to the surrounding tissues or carbonization of the vein wall. With the new system, the catheter is held in place while energy heats the catheter to a specified temperature of 120ºC. As the vein is denatured by heat, it contracts around the catheter.

With the previous-generation radiofrequency systems, as shrinkage and compaction of tissue occurred, impedance was decreased which decreased heat generation; however, this is no longer the case. Only the temperature of the catheter metal core is monitored as it delivers heat to the vessel wall in 20-second increments. Previously, the radiofrequency generator could be programmed to rapidly shutdown when impedance rose, thus assuring minimal heating of blood but efficient heating of the vein wall. In the present system, catheter core temperature is monitored and adjusts energy to keep the core at 120 º C. Heat delivered to the vein wall causes the vessel to shrink in the treated area, and the catheter is gradually withdrawn along the course of the vein until the entire vessel has been treated. This is performed in 7-cm segments.

The amount of laser or diathermy radiofrequency energy delivered to the vein is actually very small and only affects the local vein wall. Local anaesthesia is normally used. Afterwards, there may be some mild to moderate discomfort for a week to ten days, but this usually responds well to over-the-counter medications like aspirin or ibuprofen.

Results:

The ablation procedure closes the vein immediately. The improvement in blood flow happens right away. However, it may take a few weeks for the original symptoms to go away, and large varicose veins may need some additional minor treatment.

Before and after images showing marked improvement in their varicose veins, which are common viable signs of venous reflux.

If the saphenous vein has reflux, venous ablation will probably help to eliminate symptoms. The best way to test for reflux is by ultrasound examination.

Complications:

Reported complications of the procedure are rare. Local paresthesias can occur from perivenous nerve injury but are usually temporary. Thermal injury to the skin was reported in clinical trials when the volume of local anesthetic was not sufficient to provide a buffer between the skin and a particularly superficial vessel, especially below the knee. Progression of thrombus from local superficial phlebitis has occasionally been observed when compression was not used. The greatest current area of concern is deep vein thrombosis, with one 2004 study documenting deep vein thrombus requiring anticoagulation in 16% of 73 limbs treated with a radiofrequency ablation procedure.

Outcomes:

Published results show a high early success rate with a very low subsequent recurrence rate up to 10 years after treatment. Early and mid range results are comparable to those obtained with other endovenous ablation techniques. Overall experience has been a 90% success rate, with rare patients requiring a repeat procedure in 6-12 months. Overall efficacy and lower morbidity have resulted in endovenous ablation techniques replacing surgical stripping.

Patient satisfaction is high and downtime is minimal, with 95% of patients reporting they would recommend the procedure to a friend.

Sources:

http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1085800-overview

http://www.ohsu.edu/dotter/venous_ablation.htm

http://www.gehealthcare.com/usen/ultrasound/education/products/cme_end_abl.html

http://www.veins.co.uk/treatments-for-varicose-veins-EVLA.htm

Article compiled and edited by: John Sandham , Jan 2010