There have been many attempts by Government and healthcare agencies over the years to address medical technology management issues. The issues being addressed have always, broadly, involved the procurement, use, maintenance, and governance of medical technology in accordance with regulatory standards.

Evidence shows that effective healthcare technology management can improve utilisation of medical equipment and reduce costs. The World Health Organization (WHO), states that poor management leads to a lack of standardisation, and the purchase of sophisticated equipment for which operating and maintenance staff have no skills. (1)

A Government report from 2017, 'Strength and Opportunity - The landscape of the medical technology and biopharmaceutical sectors in the UK' states that the UK remains a global hub for life sciences, building upon previous success. There are now 5,649 life sciences businesses with a presence in the UK, generating turnover of over £70bn and employing nearly 241,000 people.Life sciences in the UK continues to grow across all key performance indicators, with a 2.4% increase in employment and 9.3% increase in turnover. This equates to 5,700 new jobs and an additional £5.9bn in revenue over the course of 12 months. For the first time, employment in medical technology overtook biopharmaceuticals, with new and emerging segments within the life sciences sector coming to the fore. Digital health added an extra 1,100 jobs this year alone, bringing employment to over 10,000 and generating £1.2bn in turnover.

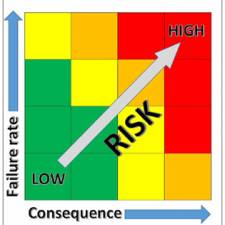

The medical technology market will continue to grow year-on-year, saying 'the medical technology market is estimated to be worth >£480bn in 2023. Revenue is expected to show an annual growth rate (CAGR 2023-2027) of 4.91%, resulting in a market volume of £582bn by 2027. This growth is driven by the ageing population and the per capita income increases in healthcare expenditure across developed countries'. This statement highlights the growing need to acquire technology, and alongside that increased costs, risks, and regulations. It is, therefore, imperative that the procurement of devices is done in a way that reduces risk and cost.

Over the last 30 years….

In 2004 a National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) project report across multiple NHS sites identified links between purchasing and clinical incidents. It said: 'The project identified that uncontrolled purchasing and device management, in the absence of competency-based training, were contributing factors in causing incidents.' (2)

A National Audit Office report in 1999 also raised concerns about equipment management and stated that Trust should introduce a standardisation policy to deliver safe devices management and financial savings. (3) Uncontrolled purchasing and device management, in the absence of competency-based training, were found to be contributing factors in causing incidents, according to an NPSA research project.

Concerns about medical devices management and policy are not new, but since 2010 they have been regulated under The Health and Social Care Act, regulation 15, which specifically relates to the safety, and suitability, and safe use of medical devices. (4)

As can be seen from figure 1, it can be extremely difficult to manage standardisation of devices into a hospital if the routes for acquisition are not carefully managed.

As can be seen from figure 1, it can be extremely difficult to manage standardisation of devices into a hospital if the routes for acquisition are not carefully managed.

The NPSA medical devices research project also showed that many organisations were operating an inefficient device management policy. It also highlighted the medical device technology risks from poor management, stating: 'The purpose of this review is to highlight the relationship between the numbers of faults reported (120) and the episodes where no fault was found (30).

The findings highlight that in 25% of the episodes the device was wrongly reported as faulty. The data for the remaining 75% did not reveal the nature of the fault and it is likely that the device 'fault' was not a failure issue but more probably a user/handling problem. This is indicative of poor training and device management.

The data also highlighted that the incidence of devices being damaged is extremely high. This is indicative of poor device management systems such as non-standardised stock and decentralisation.

It was also highlighted that nearly one-fifth of all infusion device stock, across all pilot sites, was more than ten years old. This could have serious patient safety implications if such devices are used for applications that require a high specification device.' (2)

Hospital management responsibility

The hospital needs to be able to deal with internal and external demands on device management by implementing a systematic approach that can deliver best practice through an effective policy. This is important to ensure that selection, use, and maintenance of all devices is carried out to meet the clinical needs of the patient, and the external regulatory demands.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) refer to The Medicines and Healthcare Regulatory Agency (MHRA) within the standards and regulations, specifically with regard to 'Managing Medical Devices - Guidance for Healthcare and Social Services Organisations. (5)

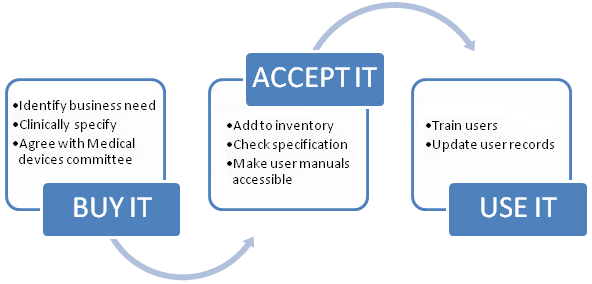

As shown in figure 2, all hospitals must operate in accordance with UK laws to implement and monitor a medical devices policy to: procure equipment that is safe and meets the UKCA manufacturing regulation; we must train users; maintain equipment; and have a medical devices committee.

According to the WHO 'Data shows that policies, strategies, and action plans for medical devices are being developed in member states... Recommendations from the first global Forum on medical devices in 2010 will continue to raise the awareness of the crucial role that medical devices play in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease and rehabilitation. The hope is that the higher profile of medical devices will translate into better healthcare for the global population, allowing them to enjoy a better quality of life.' (6)

Organisational responsibilities are described by the MHRA in 'Managing Medical Devices - Guidance for healthcare and social services organisations, which says 'Responsible organisations should appoint a director or board member with overall responsibility for medical device management. There should be clear lines of accountability throughout the organisation leading to the board. These lines of accountability should be extended, where appropriate, to include general practitioners, residential and care homes, community based services, independent hospitals providing services for NHS patients, managed care providers, PFI organisations and other independent contractors. It is important to establish who is accountable, and where there is a need for joint accountability arrangements.' (5)

The device management policy needs to cover the selection, acquisition, acceptance and disposal of all medical devices, training of all those who will use them, decontamination, maintenance, repair, monitoring, traceability, record keeping and replacement of reusable medical devices. The hospital also needs to carefully manage the acquisition of medical devices. With regard to procurement and acquisition of medical equipment, the MHRA says that policy should include the need to:

- Establish advisory groups to ensure that the agreed acquisition requirement takes account of the needs and preferences of all interested parties, including those involved in the use, commissioning, decontamination, maintenance and decommissioning.

- Ensure that the selection process takes account of local and national acquisition policies. E.g. whole life costs, the method of acquisition, and the agreed acquisition requirement.

As Figure 3 shows, clear processes need to be put in place for the acquisition of devices. The Robert Francis Inquiry into failures at Mid Staffordshire NHS Trust: 'As at December 2011, the evidence was that there was no routine follow up of compliance, unless the information suggested non?compliance with an essential standard. The CQC attributed this in part to their not having relevant expertise, particularly in relation to the safety of equipment. It (the Trust) argued that to take on such a role would deflect it from its core activities'. (7)

The Robert Francis Inquiry also discussed a lack of ownership and weak management: 'The problems identified included: Failure to achieve waiting list targets; Loss of consultant staff, citing lack of management support, equipment deficiencies, poor theatre management, over reliance on agency nurses and waiting list initiatives at short notice leading to "intolerable" strains and a "general deterioration in standards"; A failure to remedy issues about referral letters in spite of the matters having been raised over two years; Lack of management commitment to undertake agreed tasks; Lack of management coordination between Trust management and clinicians; Lack of management action to ensure key objectives were delivered. (8)

The importance of having medical devices management expertise able to lead on developing and implementing medical devices management policy within the hospital is essential to achieve regulatory compliance. Lack of management commitment, lack of management action, and lack of expertise can all contribute to the organisation being unable to comply with regulatory standards. In order to ensure compliance with the internal and external demands, there must be a policy with regard to medical devices management monitored by a Medical Devices Committee (MDC).

It is usual that the MDC is held responsible for ensuring that procurement, training, maintenance, and governance of medical devices is compliant with the needs of the organisation, and compliant with the regulations and standards of the CQC and the NHS NHSLA. The committee members are selected to ensure representation of a wide range of professional practitioners that are in involved with medical devices - whether that be buying, using, maintaining, or managing those devices.

There are many regulations which impact on medical devices policy. The issue with regulations, however, is that unless the organisation has mechanisms in place to deal with implementation, these regulations are ignored, and the hospital could be seen as breaking the law.

Poor procurement leads to variation and ultimately higher risk to the patient. This is recognised by research carried out by the WHO. It says 'A number of studies have shown that between 39% and 46% of adverse events resulting from misuse of medical devices take place in the OR (86-89). In most of these studies, the cause is only indicated as (device) operation related... Variation in medical devices between hospitals (and even within the same hospital) is one of the causes of these accidents.' (9)

Conclusion New technologies are entering medical practice at an astounding pace. This is motivated, in part, by patients who increasingly expect minimally invasive procedures. The 'side effects' resulting from the introduction of new, often-complex technology in health care, however, can be considerable - both for patients and health professionals.

The consequences of the increased complexity of technology used for the treatment of patients can be:

- The devices are often not well designed for the medical environment in which they are used.

- The user is often not trained properly to use the devices.

- The new procedures can result in long learning curves for health professionals.

These facts can influence the outcome of care. It has been shown that it is valuable to develop a standardised methodology for the evaluation of the quality of medical devices and the analysis of complications resulting from their use. It is better that new equipment and instrumentation not be introduced without a thorough evaluation of its functionality, followed by monitoring its use in clinical practice. These evaluations can be facilitated by a biomedical engineer or similar healthcare professional. If the benefit of an instrument or device cannot be proven through these assessments it should not be introduced.

Standardisation of equipment can solve many user problems and this measure has been used effectively by aviation and industry. Training and continuing education are important components of standardisation, to ensure safety. Any programmes standardising medical practices and the use of medical devices could include training curricula, including credentialing methods for the post-training period. According to the WHO, implementing such measures as part of an overall programme of standardisation will help to reduce errors and improve care.' (9)

Training is considered a high risk by Government, which has resulted in the introduction of regulations. The WHO, however, recognises the benefits of medical equipment training in their paper 'Increasing complexity of medical technology and consequences for training', but also point out the risks of underestimating the importance of training, saying: 'The influence of the operator on the effective and safe application of medical technology is generally underestimated. In an investigation on incidents involving defibrillators in the US (two), it was concluded that the majority of the incidents were due to incorrect operation and maintenance. A study of 2000 adverse incidents in operating theatres in Australia showed that only 9% were due to pure equipment failure (nine). In two reports on the use of critical care equipment by nursing staff, 19% (10) and 12.3% (11) of nurses, respectively, indicated that they had used equipment improperly, which had consequently harmed a patient'. (9)

One strategic objective of the WHO is to ensure improved access, quality and use of medical products and technologies. This objective, together with the World Health Assembly resolution, forms the basis for establishing the global initiative on health technologies, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

The WHO has two specific objectives in mind:

- To challenge the international community to establish a framework for the development of national essential health technology programs that would have a positive impact on the burden of disease and ensure effective use of resources;

- To challenge the business and scientific communities to identify and adapt innovative technologies that can have a significant impact on public health.

A recent independent report by the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch NI-004773 entitled: Access to critical patient information at the bedside, identifies the pitfalls around poor policies and weak management.

The HSIB found that misidentification of the Patient, and limited access to critical information about the Patient at the bedside delayed his treatment, and this led to him not receiving CPR, and the patient died. The core conclusions of this report point out the risks of poor data recording and the need for better technology and policy making, to help improve practice, and ultimately improve care.

Technology supporting identification - ‘Staff told the investigation that handheld devices, via the electronic observation system, had a handover function. However, this was not used as staff preferred paper’. A core component of this report is the discussion of how ‘Verifying CPR recommendations at the bedside’ must be achieved, but there appears to be a wider issue highlighted - how can any data be verified as true if staff are recording data in their preferred way (on paper) and not in accordance with the Trust policy via the electronic patient record? if there is a policy, it must be understood and audited.

‘Equipment issues related to the amount available, faulty equipment, poor battery life, and small screens making reading information difficult. The fixed positioning of desktop computers and limited availability of laptops also meant staff were not always able to have a computer with them at the bedside to access the EPR’

Most of the NHS hospitals I visit have issues with under investment in technology. In private industry, the companies that invest in good quality technology reap the benefits. The government need to recognise that there must be a significant investment in technology if they are to achieve a step change in the way the NHS operates. There has been limited investment in technology, but nowhere near enough to deliver on the governments aspirations. The NHS needs £Billions – just for technology, but it is only worth spending this money if the clinical staff expected to use it are trained, and fully understand the benefits.

‘Low-technology displays of patient information seen by the investigation included whiteboards, laminated paper, and posters. The investigation found variation in where and how these displayed information at bedsides. Variability included position, visibility, readability and legibility. The investigation observed situations where they were unable to read information’

This is just another example of some NHS organisations still operating in ways that they did 20+ years ago. Management and policymakers are responsible for ensuring that their Trust operates efficiently. Poor practice can occur where there is poor policy; or lack of adherence to policy – i.e. poor management.

‘The investigation reviewed 12 resuscitation policies and 8 patient identification policies from hospitals in England. None of the policies directed staff to check patient identity during CPR, although one did note the importance of establishing identity at the earliest opportunity. Each resuscitation policy referred to the need for a ‘valid’ CPR recommendation, but did not clarify what a ’valid’ CPR recommendation is’

Although this report focuses on the risks of what can happen if a patient is wrongly identified, there are many other points that can be picked out if one reads between the lines. The NHS has problems with –

- Policy making

- Policy delivery

- Under investment in technology

- Lack of training in technology

Until we have managers that are trained to deliver in accordance with ratified policies; and investment in up to date technology - with users that are trained to use it, then we can expect the level of clinical care to be less than it could be, and the NHS to be less efficient than it should be.

References

- Lenel, A., Temple-Bird, C., Kawohl, W., & Kaur, M. (2005). How to organise a system of Healthcare Technology Management.

- National Patient Safety Agency. (2004). Standardising and centralising infusion devices. London: NPSA.

- National Audit Office. (1999). The Management of Medical Equipment in NHS Acute Trusts in England. London: NAO.

- Care Quality Commission. (2010, March). Regulation 16 Outcome 11 Safety, availability, and suitability of equipment. Retrieved Dec 2010, from http://www.cqc.org.uk/_db/_documents/PCA_OUTCOME_11_new.doc

- Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. (2006). Managing Medical Devices: Guidance for healthcare and social services organisations. DB2006-05. London, UK: MHRA.

- World Health Organization. (2011). Development of Medical Devices Policies. Switzerland: WHO.

- Francis, R. (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry Volume 2: Analysis of Evidence and Lessons Learnt. London: The Stationery Office.

- Francis, R. (2013). Report of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry Volume 1: Analysis of Evidence and lessons learnt. London: The Stationery Office.

- World Health Organization. (2010). Increasing complexity of medical technology and consequences for training and outcome of care.